Let the dead die, so they can live on in us!

How should we live when confronted with death?

It is an omnipresent fact that, someday, all of us will perish. You will die, your family will die, and eventually, even the universe will cease to exist. The question then remains for all of us: “How should we live?”

During the 2020 Pandemic, our society came to the collective agreement that to live was to survive, no matter the cost.

In order to survive, we taped up and shut down playgrounds; we left the old to die alone, unconsoled; we imposed Covid-curfews; we put the elderly on medical ventilators; and we shut down schools and small businesses everywhere. All the rules that were imposed from above, like lockdowns, vaccine mandates, masking, and social distancing, were all accepted, and enforced so that we could ‘save lives’, and ‘stop the spread.’

Looking back on all this in retrospect, I ask myself: “what if we made life meaningless by fighting off death?”

I won’t make a case for or against certain Covid-policies in this piece. That isn’t my aim. Instead, the goal here is to elucidate the ways in which death, and pain, are essential aspects of a well-lived life.

Here I say: let people die.

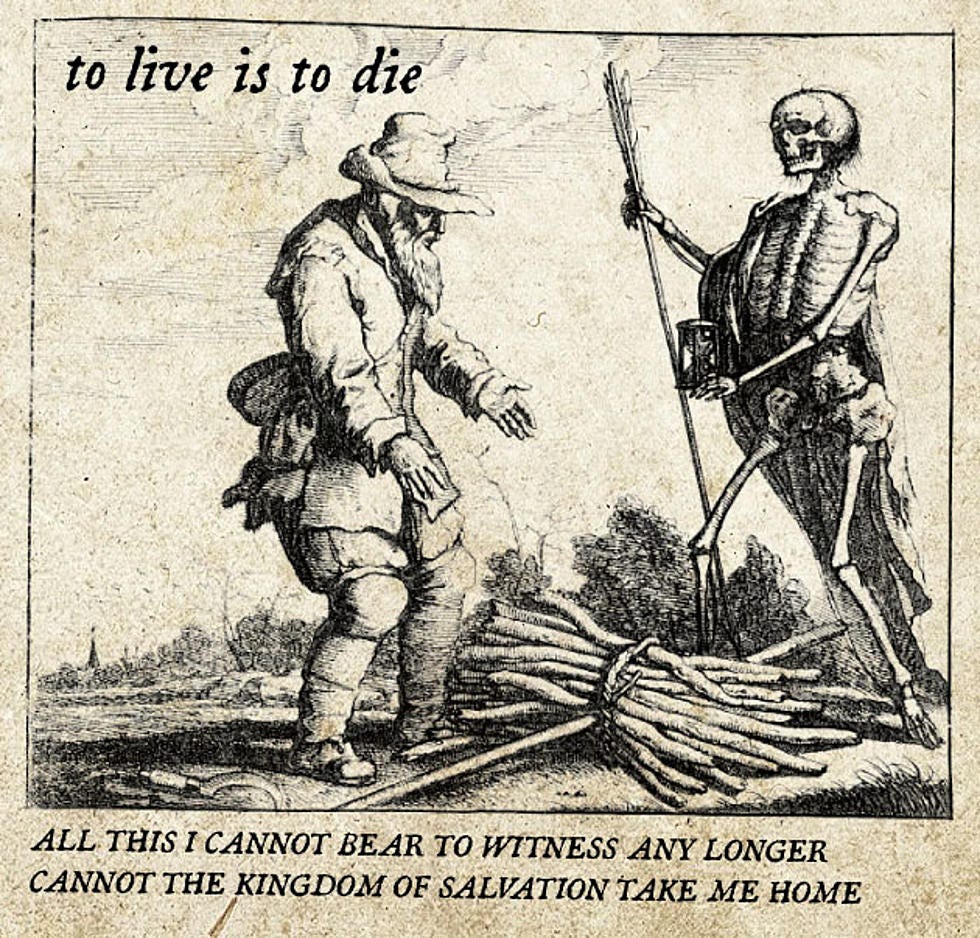

To live is to die.

All of us think we can cheat death, and push it away as somebody else’s problem.

In Phillip Larkin’s poem, Ambulances, he describes an idyllic scene in a city. Children are “strewn on steps and roads”, women are shopping—everybody goes about their daily business in a state of blissful ignorance. Amidst all of this, however, lie the sick, who are quietly ‘stowed away’ on stretchers off to their graves.

The ambulances that pass by, carrying the dead, are “closed like confessionals.” Yet, as Larkin writes, they give back “none of the glances they absorb.” Within those vehicles are individuals with a unique blend of families and fashions, memories and experiences — all of which, at one point in time, meant the world to that dead person. In the end, though, that person’s entire life has been reduced to a small, confined box that passes through traffic just like the rest of us. All we can give is a glance and look away. We can’t avoid death, though, or push it aside — the grim reaper is always whispering behind our shoulders. Someday, we may ride that ambulance too.

In medieval times, death loomed around every corner. Plagues ravaged entire continents, religious wars split nations apart, storms ripped through villages, etc. The life of a medieval peasant revolved around death, and the hereafter. As one Gregorian chant put it, “Media vita in morte sumus” (In the midst of life we are in death).

Throughout life, the most obvious fact for all of us is that we are born alone, and die alone. As Vladimir Nabokov once wrote, “our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.” Because of this, as soon as we exit the womb, we cry out for love, for touch. Even as adults, we need the consoling hum of a fan, or the sound of a podcast, to help us drift off to sleep. We can’t be alone in our own thoughts. It is too much to bear. What might this say about our relationship with death, with pain itself?

Pain brings us to a state of mind that is anterior to language, to the indecipherable cries we once made as babies. Dying soldiers will often beckon for their mom, right before death, for this very reason. The reality is that we will never be as close to another human being as we are to our mothers. That is why we almost always seek them out in times of need. I mean, they literally brought us into this world. They understand, deep down, from the moment they see us, that our suffering is incommunicable. They listen to our cries as children and intuit whether we need food or love, but they’ll never know exactly what it is we desire. Mothers come to recognize, as we all eventually do, that there’s only so much we can do to help others. That is why, instead of words of consolation, mothers will offer a shoulder to cry on. They know our pain is the dividing line that separates us from other people. Pain will always be beyond words. As Virginia Wolf once wrote:

“The merest schoolgirl when she falls in love has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her, but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.”

In times of despair and loss, everything seems meaningless and empty. Seeking out professional help, or the aid of friends often feels like an exercise in futility. A distressed teenager slamming the door on his or her parents reveals an uncomfortable truth: nobody will understand how we truly feel inside. Throughout history, our solutions to the incommunicability of pain have been varied. We've gone from prayer to painkillers, confession to therapy, sin to negative thoughts, etc.

Today, we anesthetize our pain with distractions like social media, partying, drinking, drugs, and video games. Clearly, our suffering is pushed aside, and seen as an afterthought. Our pain is something that shouldn’t be brought out into the light of day, especially in the company of others. Therefore, we hide it, and outsource the assistance we require to a therapist—with whom we pay—so we can suffer behind closed doors. Anybody who cries in public, especially at work, will often apologize afterward for doing so. Why should we say “sorry” for expressing our humanity?

Well, we don’t want to be a burden on somebody else; we want others to experience the happiness that we, ourselves, lack. This happiness, unfortunately, ultimately boils down to avoiding pain or maintaining a sense of normalcy. All those “how’s it goings?” that we exchange on a daily basis? They give the impression of a society composed of patients taking each other’s temperatures, but with no effort. Deep down, though, we don’t blame people for the small talk, for never investing in anybody else. Growing up, we make an unspoken pact with society that we will repress all negative feelings because seeing others in pain reminds us of our own pain, which must always remain hidden from view. This repression is the root of much self-harm, and depression, in our society. The fact that we even need to make this unspoken pact tells us that, from the get-go, we feel as though our lives don’t matter — our scars are unloved. Cutting oneself, for example, is a cry out for love, for recognition of these scars. It is a ritual, a form of self-punishment, stemming from one’s own feelings of inadequacy. It is impossible to live up to the needs of others when our innermost feelings of despair, or anguish, are ignored, or even walked over.

Regardless of whether you are a man or woman, in this day and age, you are either not good-looking enough, not rich enough, smart enough, or talented enough. Social media constantly reminds us of this fact. So often, we look in the mirror and see something wrong—either within or without—that must be ‘fixed’ for the sake of others.

Unconditional love, the type that endures through thick and thin, is fading. As a result, we are in a state of perpetual uncertainty. In a relationship, you can never let your guard down, or else your partner might leave you for somebody else — somebody who is less of an emotional investment. The more this happens, the heavier our baggage becomes. Over time, your heart starts to fill up like a landfill. It becomes harder to open up to other people, harder to feel love, and harder to feel anything. This is where depression sets in. Hopeless, we begin to ask ourselves if moving on is even possible, for “to go on means”, in the words of Samuel Beckett, “finding oneself, losing oneself, vanishing and beginning again, a stranger first, then little by little becoming the same as always…”

At the end of the day, though, when all our friends leave the party, and the lights dim, we are forced to confront something. Alone, a certain thought impinges upon our minds. What is our greatest fear, if not for our own end? That isn’t it, though. We entertain the thought of dying, on occasion, but something else occupies us more. Today, our greatest fear is an unlived life. For so many of us, an unlived life means a life without other people. When the room empties, when the store closes, we are reminded of this fact.

Anyone who works closing shifts in retail will tell you when everyone goes home, and you are alone in that silence—under the fluorescent lights—you can almost hear the reverberation, the echo, of lost voices. Grocery stores are often bustling with activity — machines beeping, music playing in the background, and people rushing to get their groceries. When all of this activity ceases, the fear of missing out—the fear of being deprived of connection with others—suddenly returns. The loneliness I am describing is palpable no matter where you go. It’s written on the face of the homeless man hiding in shame outside a store, who watches solemnly as you pass by; it’s evident in those brief moments when, upon stopping at a streetlight, you make eye contact with the stranger next to you who drives home, alone, in silence.

It's like those moments as a kid when you were all alone in bed, and heard the rustling of branches, felt the breeze of a half-open window, or the slight movement of a curtain. “Is something there?”, you often thought. That mixture of fear and curiosity usually prompted you to hastily cover your head with the bedsheets or to run into your parent’s room. I often reflect on these moments, and ask myself: “what was I running from?” Thinking about it now, I can’t help but think I was trying to escape from myself, from my own thoughts — the fact that I’m alone.

The life stories we seek to craft offer us an escape from this child-like feeling of isolation. Every goal we set, every decision we make, is usually informed by the desire to craft a narrative that’ll one day comfort us on our deathbed. Therefore, we create a “bucket list” of experiences that we hope to have: traveling the world, witnessing new sights, forging new relationships, accomplishing new things, etc. Mountains have to be scaled, exams passed, career ladders climbed, and places visited and photographed. It is expected that, if we take good enough care of ourselves, that quantity of experiences will enable us to achieve happiness, either now or later. We all know that life can be taken away from us at any moment, so the impulse is to use it up, to live it quickly.

As a result of this, we have to be constantly aware of what is missing in our lives. We must always remain mindful of the people, experiences, and things that remind us of our unrealized potential. Happiness, as our Declaration of Independence famously said, must be pursued, or willed into existence. That happiness is always the light at the end of the tunnel which is forever out of reach. As a consequence, we must pressurize the world to be there for our benefit, and other people must cooperate with our wanting.

As Oscar Wilde once said, though:

“There are two tragedies in life: one is not getting what you want. The second is getting it.”

None of us would pursue happiness unless we’ve experienced moments before when we told ourselves: “I’m really living.” Some of these moments might include the sight of a newborn child, a first kiss, or accomplishing a new goal. In those moments, you felt truly present. Suddenly, all of your worries receded into the background. You were alive.

All of these beautiful moments, however, are fleeting. You can’t summon them, even out of some herculean effort. Oftentimes, the happiest moments in our lives arrive when we least expect them, like a butterfly landing on your finger on a warm summer day. Think of moments like that — what do they remind you of? Do you still remember the first snowfall on a late autumn or winter day, when you were a child? The joy you felt during the first white Christmas? What made these events so special? Snow can’t be forced into existence, or even reliably predicted. It’s unexpected. Like our favorite sports team making an incredible comeback, snow is an unexpected gift, one that can’t be willed into existence.

As Rusa Hartmut wrote,

“Our relationship to snow reflects the drama of our relationship to the modern world as in a crystal ball. The driving cultural force of that form of life we call “modern” is the idea, the hope and desire, that we can make the world controllable. Yet it is only in encountering the uncontrollable that we really experience the world.”

During the pandemic, we sought to remake the entire world in our image, to control it. In an effort to survive, we shut down the entire world economy, forced people into their homes, and shut down schools and businesses, all in an effort to stop an invisible enemy. Was the invisible enemy a virus, or a version of ourselves that, amidst all the tumult and chaos, disappeared into thin air?

When I ask myself this, I think about when I was a child, when I sensed the invisible presence of something behind those closed curtains, that half-open window. What was I afraid of? What was I running from? During the pandemic, the virus brought back that child-like sense of panic, that mixture of fear and curiosity. We sought to distance ourselves from others, to cover their faces with masks, to see ourselves, and our neighbors, as potential contagion vectors. That invisible enemy that we couldn’t see, that we structured our entire lives around avoiding, was us.

In a way, Covid is a reflection of who we are now. As Byung Chul Han writes in The Palliative Society:

“In our preoccupation exclusively with survival, we are equal to the virus, this undead creature that merely multiplies, therefore survives, without living.”

CONCLUSION.

When I think about what it means to live, I think of the moment my grandmother passed away. Shortly before she died, I told her what she had told me, namely, that I would “see her on the other side.” When she passed, the nurse checked her pulse, and declared her time of death to be “7:47”. This number was significant to our family, for one very important reason: it reminded us of our grandfather, who had flown 747 jets while he was still alive. Every time the clock hit that time, my grandmother would blurt out: “it’s 7:47!” Upon hearing that she has passed at this time, our entire family felt a jolt of joy, like we had received a message from Norma Austin, who was no longer with us.

At that moment I realized that life, all of our experiences and memories, are unexpected gifts. And death is one of them. It is not something to be looked down upon. It raises us up.

I wanted to thank her for this gift, for the life she had lived, for everything she given my family and I. When everybody left, and I was alone with my grandmother’s dead body, I kissed her forehead. It was scary, sure. I was here with my grandmother, whose face was always smiling or laughing. Now, I was looking at her corpse. She was gone. When my lips touched her forehead, though, I kissed what we both called the other side. I stood at the horizon of our world, in direct but ineffable contact with that which lay beyond it. At that moment, I was alive. She gave me that gift.

Looking back on it now, reflecting on this experience, I can’t help but think of Michael Angelo’s Painting “The Creation of Adam”, and the meaning behind it. Angelo had designed the panel of man’s creation with the fingers of God and Adam touching each other. The Cardinals overseeing the painting’s creation said the fingers should not be touching, and that God’s finger should be tended to the fullest. In the end, Adam’s finger was contracted at the last phalanx, creating a small separation between man and God. Why was this subtle change made?

In that tiny space that lies between ourselves and God, in that brief interstice between the two eternal darknesses that is our life, lies our freedom. That small distance between ourselves and the other side is time itself, and all the moments we create within our brief span of existence. The preservation of that distance is life-giving. When I kissed my grandmother’s forehead, I felt her absence. I realized that, wherever she was, it was far away. This distance, however, paradoxically, brought me closer to her, to my own life. I was communicating, in some strange way, with the world she had sent a message from. This was possible precisely because she was gone. She had given me the gift of life, and I realized that, now that her’s had concluded, I could also face death.

At any time, we can reach out to God, stretch out our fingers, and come close to touching him. But we can only truly feel his presence if we know, deep down, that we are alone, and that He, Himself, is unreachable. This may sound paradoxical, but as Zizek once put it:

“In reply to the believer’s love for Him, in reply to the hands that the believer stretches toward Him, God himself changes into a lover and reaches back toward man—concealing thereby the abyss of the Otherness that no sacrifice could appease.”

In the end, that last phalanx must always remain contracted, until God reaches out from the other side to touch us at time’s end.

Our freedom consists not of learning how to live, but rather of learning how to die. I think of that Roman soldier who Oswald Spengler spoke of, “whose bones were found in front of a door in Pompeii, who, during the eruption of Vesuvius, died at his post because they forgot to relieve him.”

Instead of running away from the ashes and flames, instead of taking the path of least resistance, he did what nobody else even told him to do — he stood tall and died. It is our duty to do the same. We must pick up our cross, face the unknown, and never look back. Don’t run from death, from solitude, from pain. These things may separate you from others, maybe even from God himself, but remember this: Christ died for our sins, and he was closest to humanity during his greatest moment of doubt. Even Christ, the Son of God, cried out to the Lord

“Why hast thou forsaken me?” (Psalm 22:1).

Here I say: Let the dead die, so they can live on in us!